As the European Union (EU) has been shaping its attempt to become a global security actor and provider, it has repeatedly stressed the importance of certain principles and norms both at home and in its foreign policy. In academia this was mirrored in the concept of ‘Normative Power Europe’ famously coined by Ian Manners, which highlights a projection of European influence in which norms guide the way Brussels operates in the international arena. Nevertheless, throughout the decades, the EU has had to confront a series of international events which have often complicated the unconditional adherence of European decision-making in foreign affairs to its normative commitments. Not too long ago, events such as the conflicts in the Balkans or the war in Iraq demonstrated that security interests can, at times, override European consistency when it comes to international law.

Europe’s official discourse has likewise changed according to the many global challenges that the EU has had to face. In more recent years, the Union has become an actor guided by the idea of ‘principled pragmatism’ and that has, moreover, increasingly recognized and accepted its geopolitical nature. While good on paper, such a position has resulted in what can be seen as a growing tension between the EU’s normative pillars and the need to pursue its interests and those of its Member States within a rapidly changing international environment. This tension has become problematic in the context of the European policy towards neighboring countries, but it has also had consequences for Brussels’s relations with Asia and particularly East Asia. These relations are key due to the ascending importance of the latter regions in today’s international geopolitical context.

European foreign policy towards its neighborhood is indeed a great example of how the EU has attempted to secure its borders and beyond by mixing normative-embedded concepts such as the conditionality of ‘more for more’ (meaning that the EU will pursue stronger partnerships with neighbors that make more progress when it comes to democratic reform), with questionable agreements such as the one on migration with Libya. Such policy has also shown its limits considering the aftermath of the events of the Arab Spring, not to mention the great incongruence between the call for peace in the Southern vicinity and the continuous selling of weapons by European contractors to many of its countries and regimes. On the Eastern neighborhood, the war in Ukraine has too demonstrated, however uncomfortable it may be to recognize, a failure of this approach to stabilize the neighboring region.

Europe’s balancing efforts in East Asia

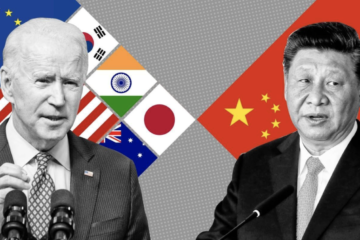

As noted before, the EU’s pragmatic side has not limted itself to the relations with the immediate European neighborhood. When it comes to its policy towards Asia, the EU has had to navigate, among other things, the difficult relationship with China. In particular, although Brussels has been vocal about denouncing the breaches of international law (such as human rights violations or infringements of sea conventions) by Beijing, the Union has also admitted that strategic partnership with the country is of vital importance to the interests of the EU. Furthermore, some European countries have even blocked certain criticisms towards China, which can be arguably traced back to a series of economic interests at play.

The complexities of this relationship have impacted, for example, the credibility of the European position on the Taiwan strait. On the one hand, Brussels adheres to the ‘One China’ principle, implying that there is only one China (including Taiwan), and that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is its only legitimate government. On the other hand, in the last few years, Europe has been more eloquent about the need to preserve the status quo in the strait. Moreover, it has also emphasized the importance of Taiwan as a like-minded partner whose democratic system of governance, respect for the rule of law, human rights, and market system need to be supported. All of this has been done while reiterating consensus on the notion of ‘One China’.

Russia’s war against Ukraine is affecting EU’s relations with East Asia

Recently, the war in Ukraine has triggered a series of mechanisms that have impacted the prioritization of immediate security concerns for Europe, as demonstrated by the skyrocketing European military spending. Nonetheless, at this point, it is clear that the impact of the war goes far beyond that. Among other regions, this war has had an indirect/direct influence on the security framework of East Asia. China has undoubtedly been watching the unfolding of the conflict, and many experts point at how this may have consequences for the tensions in the strait. Moreover, the war has pushed Russia to become, once again, close with regimes such as that of North Korea. Not only this, but in some continents like Africa, actors like Russia and China are visibly expanding their influence.

If violations of international law may have been easier to criticize in the context of the war in Ukraine, the rekindled conflict taking place in the Middle East has, once again, complicated European normative coherence. Thus, as we observe the deepening of old global divisions with the extreme violence which has characterized Israel and Palestine in the last five months, one cannot but wonder how the EU’s difficulties in keeping one foot in the normative shoe, and the other in the pragmatic and interest-based shoe will play out regarding its security relations with Asia. The security of the region has, at the end of the day, climbed in the EU’s foreign policy agenda in the last decades, as demonstrated by a series of official documents on East Asian security, the Indo-Pacific, and related activities.

Security in East Asia is becoming a priority for the EU

These actions show that Brussels wishes to become more active in Asia and East Asian security, especially considering how geopolitical competition is becoming more pronounced in the area. However, normative incoherence in other contexts will become a problem for the credibility of the EU’s policy towards a region where many of the ongoing tensions have much to do with international law. From the situation on the Korean peninsula, to the many maritime territorial disputes, China’s claims of sovereignty and the tensions in the strait, the regional security framework is characterized by a very precarious status quo upheld by (among other things) an international system of law that struggles to survive within a heavy militarized environment.

It is no secret that the EU does not have the leverage that actors like the US have in Asia. Nevertheless, it is an entity which, despite its limits, has signaled a desire to become more active in matters of Asian security. Most importantly, it is an actor that still has a voice in international affairs and that, therefore, has a certain level of responsibility. The erosion of norms as a result of its inconsistency when it comes to applying them ad hoc through its own actions and discourse will have consequences that may jeopardize the stability of regions beyond its borders, including Asia. It will also potentially picture the EU as a less credible, and thus, less relevant global actor and partner, whose incoherence may be used by forces proposing alternative systems. Finally, what is most concerning in today’s volatile and interconnected international environment is that this behavior has an impact on ordinary human lives, creating further injustices in a world where the ones who pay the highest price are always those who are the most vulnerable.

Laura Andrés Serpi is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the Complutense University of Madrid. She holds a bachelor’s degree in International Studies from Korea University and two masters, one in East Asian Studies from the University of Salamanca and an LL.M. in Law and Politics of International Security from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her academic field of specialization is International Relations and International Security with a focus on East Asia and particularly Korea.