As threats were exchanged between Washington and Tehran in June 2019 – shaking an already explosive cocktail of Twitter barbs, seized oil tankers and downed military drones – one unexpected figure emerged in an attempt to broker a compromise between the two; Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan. Mr. Abe became the first Japanese leader to visit Iran since the fall of the Shah over 40 years ago, in a move symbolic of Japan’s growing desire to play a leading role on the world stage.

Though the deadlock remains, Mr. Abe’s visit highlighted Japan’s increasing diplomatic heft following decades of inwards-looking policy. For a country that since 1945 has been trying to ‘fit in’ quietly with the international community, it is now ‘standing out.’

A Changing Regional Security Landscape

The Japanese defence landscape is gradually changing to accommodate a new reality, namely the increasing geopolitical tensions in Japan’s neighbourhood. From increased defence spending and procurement to industrial de-regulation to facilitate arms exports, Japan appears to be preparing for turbulent times ahead.

Following spat after spat of foreign policy crises and a weakening American-led world order, Japan’s outlook on regional security affairs has altered considerably. The days when the deployment of an American carrier battle group seemed able to quell any dispute are on the wane. Two threats in particular have rekindled anxieties. The first is North Korea’s ongoing nuclear programme. As the Trump administration’s denuclearisation talks falter, the DRNK continues testing short-range missiles capable of reaching Japan. Secondly, and more pressing for Japan’s long-term interests, has been China’s rapid military rise and increasing boisterousness in the region. China’s militarisation of man-made islands in the South China Sea, along with its Belt and Road Initiative present signs of an aspiring hegemon.

Worryingly for Japan, after decades of acrimony, closer Chinese-Russian cooperation seems to have made a comeback as well. In late July 2019, as a joint patrol of Russian and Chinese planes penetrated South Korea’s self-declared ‘Korean Air Defence Identification Zone.’ Prompting ROK interceptor jets to use machine gun fire upon the Russian aircraft. Japan’s own fighters were also scrambled to the airs in what could have escalated into a deadly miscalculation. In the 12 months that ended this March Japan has scrambled its jets 999 times in response to aerial incursions over its territory—two-thirds of them by China and the rest by Russia.

The deteriorating security developments have matched gradual shifts in the regional balance of power and what might be called a putative arms race. Although the United States and China will dominate regional defence spending and military capability, ‘smaller’ but able powers like South Korea, India, Vietnam, even Russia are also revamping their arsenals.

Although it is hard to peg the situation in the Asia-Pacific region into traditional definitions of an arms race – spiralling defence spending and constant ‘one-upmanship’ – what is certain is that the region is seeing a vast modernisation, quantitatively and qualitatively, of naval fleets and air capabilities – in particular submarines.

The American-Japanese Security Alliance

Against this agonising backdrop, Japan has also since 2017 had to fare with the mercurial American President. Although the American-Japanese alliance has formed the cornerstone of US security policy in the Pacific since World War Two, Japan has been under constant pressure from President Trump to increase its defence spending and reshape its trade practices, lest the US abandon its ally.

Shinzo Abe tried to pull all the stops to enter President Trump’s good books. He (in)famously offered then President-elect Trump a gold plated golf club at his Mar-a-Lago resort, whilst Abe’s trade team have diligently been engaging with Robert Lighthizer to avoid economic disaster from threatened tariffs on the Japanese automotive industry.

More recently, Japan tried to placate the American President by promising to procure the Aegis Ashore missile defence system to protect itself from North Korea rockets, and increase its number of F-35 fighters.

Japan has benefited greatly from the relative stability of the region and open global commons since the Cold War — largely underpinned by pax-Americana (as evidenced by the 50,000 US servicemen based in Japan and over 28,000 in South Korea). But as the first two years of the Trump administration have threatened to upend traditional security structures, with vast changes in the regional balance of power, Japan has been multiplying its efforts at preserving the regional status-quo as well as bolster its defence strategy and industry.

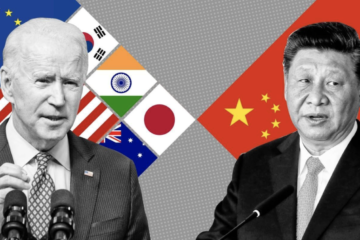

Japan has been at the forefront of diplomatic efforts, including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD, also known as the Quad), an informal strategic dialogue between Japan, India, the USA and Australia. It has also been sure to bind itself to the US to keep Uncle Sam’s ships anchored in the Pacific. If anything, the re-branding of America’s diplomatic vocabulary to call the region ‘Indo-Pacific’ as opposed to the old ‘Asia-Pacific’ term demonstrates the broadening of traditional security and diplomatic arrangements and the US’ increased focus on countering China by hopefully bringing India to its side.

Japan also continued efforts to fend-off China’s economic weight by trying to inject life into the moribund Trans-Pacific Partnership – signing a new agreement (CPTPP) in March 2018 with eleven other states.

Overhaul of Japan’s Security Apparatus

Perhaps more importantly, Japan has been overseeing major changes to its ‘hard power’ through an overhaul of its defence landscape, this even prior to the American President’s incessant calls to ‘pay up.’

In 2015, Japan’s “Peace Constitution” underwent a ‘reinterpretation’ to offset the limiting features of Article 9, under which Japan outlawed the act of war as a means to settle international disputes, armed forces designed for outwards expansion were renounced and a blanket ban on arms exports was instituted. The ‘Peace Constitution’ has come to form a core plank of post-war Japanese identity, and it is no wonder that debates over reinterpretation have been fraught with disagreement and objection.

The reinterpretation of Article 9 now allows Japan to exercise the right of ‘collective self-defense’ to defend and support allies materially if need be, along with removing the ban on exports. Greater recognition of Japan’s de facto armed forces will be determined by a planned referendum in 2020 – though support for this has been found wanting.

This August, the Japanese Self-Defense Forces asked for its largest-ever defence budget – totalling around $50 billion for the fiscal year beginning in April 2020. Japan has also called to improve its indigenous defence industry through greater local manufacturing, partnerships and increase exports of military hardware.

In terms of actual requirements, the Japanese Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) ‘Medium Term Defense Program’ published in December 2018 provides a good insight into what capabilities Japan is looking to invest in. The paper clearly outlined that procuring platforms to compete in a conflict with a near-peer competitor and countering ‘grey-zone’ activities in space and cyberspace were the priority.

One radical departure from past Japanese defence policy was the announcement that the MoD would be retrofitting its ‘helicopter carriers’ to be able to launch aircraft like the F-35 – in effect establishing Japan’s first aircraft carrier since World War Two and increasing its power-projection abilities.

In the realm of airspace, Japan is looking to upgrade its fleet of F-15s with the latest EW capabilities, along with enhancing the network capabilities of the F-2. Tellingly, the paper announced that for a future fighter programme the “SDF will procure new fighters that are capable of playing a central role in future networked warfare before the retirement of the fighter aircraft (F-2). MOD/SDF will promote necessary research and launch a Japan-led development project at an early timing with the possibility of international collaboration in sight.” Japan is heavily tipped to join the British ‘Team Tempest’ fifth-generation fighter later this year.

Given Japan’s geography, a premium has been placed on ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) to supervise the vast airspace and oceans surrounding Japan. These include increased investments in new submarines, patrol vessels, destroyers and the indigenously built Kawasaki P-1 maritime patrol aircraft. The paper also remarked that missile defence, and early warning systems will remain vital, hence the acquisition of the Aegis system.

Japanese Space and Cyberspace Security

Lastly in the new domains of space and cyberspace Japan announced the establishment of ‘a space domain mission unit’ to improve its situational awareness. In defence jargon this essentially means an observation post to monitor Japans’ space assets like satellites. Indeed, while satellites are essential to military operations, providing aerial footage, SATCOM and GPS – they are also extremely vulnerable. Prone to hacking, anti-satellite missiles and dangerous ‘proximity manoeuvers’ by malign actors directing their satellites into others, increased situational awareness should help Japan anticipate the threats. China famously launch an anti-satellite missile in 2007, provoking wide condemnation from the United States and Japan.

In cyberspace, the SDF noted it would also seek to “strive to keep abreast of the latest information including cyber-related risks, counter measures and technological trends, through cooperation with the private sector, and strategic talks, joint exercises and other opportunities allies and other parties.”

Structural Changes in the Japanese Defence Industry

Whilst the procurement of these platforms should keep Japan abreast of geopolitical developments in the short to medium term, it has also been planning deeper, structural changes to the way its domestic defence industry operates.

For decades Article 9 has also limited the Japanese defence industry’s opportunities for growth. Through a ban on international exports the industry has been limited to one customer, the JSDF, and seen an increasing reliance on the US Foreign Military Sales Program (FMS). Despite the crucial importance of the FMS program in providing the JSDF with high-end equipment, it has stifled domestic industry. Buying American ‘off the shelf’ has caused the Japanese defence manufacturing expertise to contract, and shut Japan companies from supplying parts to programmes like the F-35.

Japan hopes to rectify this by opening-up its defence industry and integrating the global defence supply chain, not least through international exports. It will suffer, however, from a lack of experience in foreign military sales.

Felix Chang, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, advises that Japanese industry should seek to integrate itself within America’s FMS supply chain for products destined to Japan. Japan could, for instance, supply parts for or assemble the F-35 fighter and the new Aegis destroyers domestically. Japanese industry’s greatest strengths do not rely so much at the moment on its ability to produce big-ticket platforms, but rather the ‘screws and bolts’ of defence.

As Jeffrey Hornung, a political scientist at the RAND Corporation explained, “if Japan is really serious about exports it should start in areas where its strengths are, which is in components and sensors, these are areas where Japan maintains a leading edge in civilian industry […] A focus on niche capabilities to begin with is how South Korea started 20 years ago and is now a major defence exporter, especially to the ASEAN region.”

Contrary to past their past policy, multiple government bodies are now encouraging Japanese companies to export and engage with foreign defence companies – as demonstrated by the Japanese MoD, Foreign Office, ATLA and Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s support for DSEI Japan – an international arms trade show modelled on the one held every two years at the ExCel centre in London (it will in all likelihood trigger the same furore from protestors).

While Japan remains in the early days of its defence remaniement, the impact of the Pacific’s deteriorating security environment on Japanese defence policy is clear. Bigger budget, bigger ships, more state-of-the-art aircraft, bigger investments in cyber and space, a radical re-shaping of domestic industry and multiplying diplomatic efforts as Shinzo Abe criss-crosses the globe.

Not mentioned in this article, but with all the potential to scupper Japan’s ambitious plans, are a whole host of unresolved issues. From the ongoing conflict with South Korea (culminating in the self-inflicted wound to scrap an intelligence-sharing agreement), a war-wary public, brash Japanese diplomatic gaffes reminiscent of the imperial-era and a faltering economy to name but a few.

Japan is serious about defence, but whether it can deliver remains to be seen.