Throughout the years, Japan’s China policy has been rooted in the 1974 Treaty of Peace and Friendship’s clause on ‘mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, …, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful co-existence.’ Japan has fully recognised China’s claim over Taiwan as legitimate, strictly limiting relations with Taipei and siding with Beijing during conflicts in 2004 and 2007. It has also depoliticised Tibetan independence—against domestic sentiment—and largely abstained from discussion on Beijing’s human rights record in international fora. In terms of mutual benefit, Japan was one of the earliest proponents of China’s WTO membership, one of its biggest aid donors and a significant contributor of foreign direct investment (FDI) despite political tensions. Towards peaceful coexistence, Japan has accepted China’s military capabilities in exchange for support of its own regional position, conditional on transparency and communication, and only marginally expanded its own capabilities.

If Japan were adopting a balancing strategy, we would expect decisive deviation away from these trends. Looking at three key issues, we can see how Japan’s foreign policy disappoints mainstream balancing expectations.

Consider Japan’s approach to China’s recent claim of sovereignty over the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands in the East China Sea. The islands are a strategic asset which defines the air defence identification zones for each country and which provides access to underwater deposits of oil and gas. Despite attempts by Beijing to escalate the dispute and Japan’s outspoken frustration, it has withheld military mobilisation. Far from capitalising on China’s assertiveness in pushing to cement the territorial status quo, Prime Minister Abe issued moderate responses, refrained from drawing excess international attention, and held on to Japan’s non-acknowledgement of the dispute, eventually normalising relations with Chinese President Xi Jinping in November 2014. Although a hit to its regional status, Japan has chosen to accept an equilibrium of naval presence around the islands in return for stability.

But what about Japan’s new defence capabilities and security legislation? Despite outcries that Japan was re-militarising, Abe’s reforms merely enable it to honour two commitments: 1) participation in humanitarian security missions protecting UN-led troops and civilians, and 2) protection of the status quo in the Asia-Pacific. The reforms give Japanese security actions a legal anchor and bring its negative pacifist attitude up to date with the proactive pacifist worldview that other liberal powers had adopted after the Cold War. It represents a conviction that global peace can only be achieved if responsible states intervene robustly to safeguard the international order. Most importantly, they include extremely strict parliamentary controls, disabling any potential overstep of executive power.

In comparison to other US allies, Japan remains far less capable and lacks the power-projection assets necessary for a balancing strategy. The recent increase in defence spending merely offsets added vulnerability in the Japanese south from China’s improved standing. As outlined in the 2013 National Security Strategy, Japan does not aim to stop China’s ascendancy to global prominance but rather to deter direct threats to its security and the regional status quo, for which it seeks continued, but not significantly increased US support. Indeed, its much talked-about 2015 revision is practically not far from being a reassurance of the existing agreement. These intentions are also reflected in Japan’s recent establishment of a security communication mechanism with China to ease tensions.

Lastly, despite a slowing Chinese economy and soured relations over the Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands, regression in imports from China has been a microscopic 0.029% over five years. Japanese FDI in China has mostly correlated with FDI in Asia and even rose despite a regional contraction in 2016-17, in support of Beijing’s “Made in China 2025“ strategy. Neither government has acted to deter Japanese business from investing in China. Recently, both sides have even pledged to accelerate talks on a bilateral free trade agreement.

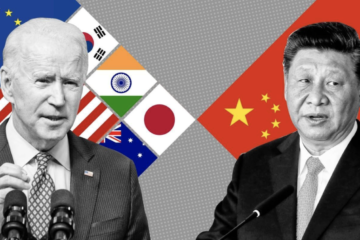

There is no indication of a change in Japan’s foreign policy towards balancing China. Yes, Japan has adopted some changes under Abe, especially vis-à-vis its previous position that was militarily vulnerable, legally confused and restricted, and somewhat isolated. Nevertheless, its actions are nowhere near those necessary to credibly and effectively contain China’s development. This means we have to re-think the prevalent security competition scenarios in the Asia-Pacific. After all, the great showdown of a grand alliance comprising the US, Japan, and South Korea with China might not be as inevitable as Mearsheimer and his fellow realists insist.

Here are some clues as to why Japan is not balancing against China.

Most importantly, Japan benefits enormously from China’s economic upswing. China is Japan’s largest source of imports and second most important export market. The fact that China is the primary destination for Japanese FDI shows its importance to a struggling Japanese economy. Limitations on trade or tariffs would only hurt Japan’s position, especially amidst practically dead domestic consumption and major demographic challenges.

But there are also political reasons. A majority of the Japanese public has no interest in the sort of power competition characteristic of the US or China and retain strong affinity with its post-war pacifist identity. Completely alienating China would also be useless to Japan in solving other security challenges, such as the North Korean nuclear threat.

All this is not to say that Japan will not engage in future balancing against China.But for now its strategic outlook remains unchanged. As Abe emphasised in 2013, Japan is interested in maintaining adequate security and a ‘mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests,’ within the liberal international order and with improved crisis management capacity in the region.