SEOUL, South Korea – The gleaming headquarters of Samsung is a potent symbol of modern Korea. But the global conglomerate has found itself in the thick of an intense crossfire as Japan and South Korea descend into a trade war over historical disputes from the previous century.

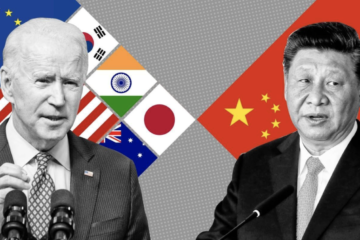

For decades, Japan and South Korea have been major trading partners, with $84.6 billionworth of trade flowing between the two nations in 2018. Ranked 3rdand 11threspectively by GDP in the same year, both are key allies of the US in checking a rising China and exchanging sensitive information on North Korea. Despite these shared geopolitical interests, the Asian powerhouses have turned against each other over this summer.

Events

On July 1st2019, the Abe cabinet announced its decision to impose restrictions and introduce a licensing process on exports of the following chemicals to South Korea in semiconductor manufacturing: fluorinated polyimide, hydrogen fluoride and resists. These high-tech materials are used to manufacture chips and displays of smartphones and televisions. Japan currently produces 90% of the world’s supply of fluorinated polyimides and South Korean companies, such as Samsung and SK Hyink, have deep supply chains in Japan. Samsung Electronics is the leading manufacturer of DRAM chips, accounting for 40%of the nearly $100 billion market, whilst SK Hyink has a 31% share. While chip production is just one market that Samsung dominates, the company alone accounts for 15% of South Korea’s total GDP, which highlights the importance of Samsung to the Korean economy. By introducing the licensing process, which requires individual export approvals for the chemicals (which could take as long as 90 days), the Abe cabinet have delivered a reeling blow to South Korea’s economy.

Samsung has acutely felt this economic bludgeoning, with Vice President Lee Jae Yong asking local vendors to stockpile three months’ worth of the Japanese chemicals after failing to receive assurances that supplies would flow unabated following his trip to Japan. One senior Samsung official commented that “It is one of the worst situations we have ever had. Politicians take no responsibility for the mess, even though it has almost killed us“.

For Japan, the chemical exports are estimated to be worth $500 million a year. Eo Gyu-jin, an analyst at eBest Investments & Securities , points that “Japanese companies would find it hard to restrict exports for an extended period, as Korean companies contribute to a considerable share of their earnings.” And Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, meanwhile, pledged to ‘closely watch the impact on Japanese firms’, acknowledging that this move also negatively affected Japanese companies. But a quick comparison of which country loses more in terms of trade ($500 million v $71 billion) shows South Korea in the losing seat.

Senior Japanese officials in Abe’s cabinet, such as Trade Minister Hiroshige Seko and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga have cited “national security”as the official reason for implementing this measure, both to the Japanese political constituency and the WTO. Although they have not released evidence, Japan insists that South Korea exported hydrogen fluoride to North Korea, thereby eroding the “mutual trust” that underpinned the exports system. South Korea firmly rejects these charges, instead arguing that this weaponization of trade was a clear, yet unspoken “retaliation” as a way of settling historical disputes, which Suga has denied.

Tensions escalated further on August 2nd, when the Abe cabinet removed from South Korea from its ‘whitelist’ of 27 countries. The ‘whitelist’ is composed of trusted export countries that receive preferential treatment through simplified export procedures. This symbolic removal has inflamed much of the South Korean public, who see this as a sign that Japan is not sincerely apologetic over war crimes committed under its colonial occupation of Korea. Anti-Japanese sentiment has solidified into a ‘Boycott Japan’ movement. Many South Koreans have stopped buying Japanese products, ranging from cars to beer to cosmetics. 23,000retailers, for instance, have stopped importing Japanese beer, and a surge in patriotism has seen sales of Korean beer rise by 19 percent. There have also been widespread cancellations of trips to Japan, with Asiana Airlines (a Korean airline company) reporting that there was a 30 percent fall in reservations in August compared to last year. In the most extreme case, a Korean man angry over the first round of trade restrictions set himself on fire.

With such sentiment at the public level, Moon Jae In’s cabinet responded tit-for-tat on 22ndAugust by alerting Japan of its intention to withdraw from the General Security of Military Information Agreement, which collects and shares sensitive military information on North Korea, a move which Japan’s foreign Minister Taro Konon has called ”extremely negative”and ”irrational”. On September 18th, South Korea removed Japan from its own ‘whitelist’.

History – Wartime Labour Compensation

Last October, the South Korean Supreme Court ordered Mitsubishi, a Japanese company that used slave labour during the colonial occupation, to pay $134,000to 10 victims. In the following month, a lower court ordered the seizure of shares valued at $356,000from Nippon Steel to be distributed to four wartime victims.

Japan argues that these rulings violate the 1965 ROK-Japan treaty which normalised ties between the two nations. The treaty saw Japan paying $300 million ($2.4 billion today), and said that all claims are “settled completely and finally.” On this ground, Japan insists that South Korea is flouting international law and justice, and thereby responsible for the breakdown in this bilateral tie.

However, the picture is not as clear cut. In 2004, the South Korean Foreign Ministry released documents relating to the talks behind the 1965 treaty. A national commission, which re-examined the clauses of the treaty, concluded that it did not cover “illegal acts against humanity”. In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled the workers had the right to sue Japanese companies, and South Korean court rulings since late 2018said the victims were not compensated for their emotional pain and suffering. In essence, Japan and South Korea have different interpretations of what constitutes ‘justice’. Consequently, more than 70 Japanese companies – including Toshiba, Panasonic and Nissan – have been caught up in these disputes.

These decisions have enraged Japanese conservatives, who, in the words of Yoichi Shimada, professor of International relations at Fukui Prefectural University, “have for some time [been] calling for Abe to take bilateral measures that make South Korea feel pain, and that is exactly what he has done”. By taking such a drastic measure, therefore, Abe has satisfied his party’s anger towards South Korea, with the Japanese House of Councillors election on 21 July. This move therefore appears to have been propelled by three things: 1) The oncoming House of Councillors election 2) Legitimate anger at South Korea for flouting the treaty and 3) A subconscious fear that South Korea’s rulings hold a degree of validity. The Supreme Court rulings occurred in October-November last year, and it appears that the Abe cabinet have been planning and waiting for the right time to settle this dispute through economic measures. If this analysis of Abe’s intention is correct, it explains why Japan did not hurt the Korean economy in December 2018, when Tokyo accused a South Korean warship of locking its radar on a Japanese patrol plane given the short time frame for planning. The fact that “national security” was cited to support unsubstantiated claims that South Korea imported chemicals to North Korea thus reflects Abe’s opportunistic grab to bury wartime compensation once and for all through economic measures, which by this time had been planned and ready for implementation.

As Bong Young Shik, an expert on Korean politics at Yonsei University said, “Everyone on both sides of the confrontation clearly knows that this is about the settlement.”

Influence

Weaponizing trade is not a new phenomenon in East Asia. In recent years, China has used trade in dealing with territorial disputes with with Japanin 2010, the Philippinesin 2012 and to protest South Korea’s installation of an antimissile systemin 2017.

But experts point to the influence President Trump’s handling of trade has had on its allies. “I would be very surprised if Japan would have done this without the U.S. doing it in the very recent past,” said Bryan Mercurio, an expert on international trade law of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

President Trump has labelled label European and Japanese cars as national security threatsand used the threat of tariffsto force Mexico into tightening its stance against illegal immigration into the United States.

“Japan is the latest country to mix trade with politics, following the U.S. and China,” said Peter Kim, a global strategist at Mirae Asset Daewoo in Seoul. “Very much like the ‘Entity List’ from the U.S. aimed at China, the measure is a continuing global trend of weaponizing trade at the expense of multilateral agreements and transparency.”

Ramifications

- Korean companies have learnt about the dangers of depending so highly on Japan for semiconductor materials, leading the Moon Jae In government to announce a plan which will invest $6.48 billion in research and development over the seven years.

- According to trade law experts, “If not one or two or three but 10 or 15 countries decide they’re going to take measures, really unilateral measures, based on some ill-defined national security exception, it devaluesthe rules.”If weaponizing trade is used too often, “there’s a real potential to absolutely destroy the entire international trading system”.

- For Korea-Japan relations specifically, “The really troubling thing about it is that it represents the increasing weaponization of these trade or economic interests to coerce another country over completely unrelated issues,” said Gene Park, an expert on international political economy and Japanese politics at Loyola Marymount University. “Japan has a lot of legitimate grievances,” he said, but trade measures are “not the right way to address them.”

- The sharp surge in patriotism and anti-Japanese sentiment has led Korean politicians to weaponize nationalism to combat the weaponization of trade. Moon Jae In said that that “we will never again lose to Japan”while Cho Kuk, a senior official, posted on SNS that “If we cannot avoid legal and diplomatic battle, we should fight and win”. Given that the Korean general election takes place next year, it is highly unlikely that the Moon administration will back down unless there is a drastic change in public opinion.

- Whilst ‘national security’ is a cover for the Abe cabinet to impose the trade embargo, their retaliation against South Korean is nonetheless based on their genuine/pseudo-genuine belief that South Korea has flouted international justice and is thereby responsible for this breakdown in order in East Asia. South Korea’s interpretation of the 1965 treaty has led its courts to articulate a different language of justice. Until both Japan and South Korea share a common understanding of ‘justice’ from the treaty, future diplomatic relations between the two countries will remain tumultuous.

- Increasing emphasis on human rights have profoundly shaped relations between Japan and South Korea

To conclude, then, Japan and South Korea, by throttling each other by the neck, have fallen into an abyss. It remains to be seen when they will climb out, and most importantly, how they will climb out.

NB: See for The Dark Statue: The Discomforting Tale of ‘Comfort Women’for another perspective on Korea-Japan relations