Latin America holds a unique position in the Climate Change and Energy transition scenario: it is responsible for less than 10% of global carbon emissions and already has an outstanding renewable source. The continent has double the share of renewables in electricity generation compared to the world average – 60 and 30%, respectively (IEA). This essay contends that Latin America must rely on more than its inherent advantages to avoid falling behind in the Climate Change race

Hydropower has been the foundation of the region’s electricity supply for decades. It provides the bulk of electricity in Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, Paraguay and Venezuela. The fact that hydropower accounts for 40% of the continent’s general energy source is a key factor in the region’s rare success in achieving high levels of human development (measured by life expectancy, literacy, and income) with minimal greenhouse emissions. Still, hydropower is vulnerable to drought as rain patterns shift and become more unreliable under likely warming scenarios. Thus, new low-carbon pathways of development, which emphasize renewable energy, desperately need to be developed in the region. Luckily, Latin America holds all necessary conditions for wind and solar, is a reference for the use and production of biodiesel (pioneering the technology), and holds the world’s largest share of minerals critical for clean energy technologies (like Copper and Lithium).

Once again, geographical resource distribution is favourable to Latin America. However, this natural privilege does not mean that the continent is exempt from transitioning or need not be concerned about the swift changes caused by global climate change mitigation efforts.

Furthermore, despite being on the promising side of the solutions for climate change, Latin America remains a focal point for experiencing its negative consequences more severely. The continent constantly witnesses the fury of climate change and an unbalanced El Niño, as we saw recently by the fires that claimed over 130 lives in Chile’s Valparaíso region. Disappointingly, these events receive little coverage in the mainstream media of the Global North. Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident, as the region is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events, like floods and hurricanes: disasters which sadly become routine to the inhabitants of the region. The situation is critical and gives rise to negative self-reinforcing cycles. A recent study by the World Bank highlights that these disasters disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing inequalities and hindering development efforts.

Whether it is Latin America’s world-desired capabilities to transition to a net zero energy source or its greater vulnerability to the effects of climate change, both aspects lead to a single conclusion: it’s time to take bold actions while we are still in the turning point toward a new global economy.

Carbon mitigation actions from economic superpowers are dictating the future of trade worldwide, showing both strategic interaction and distributive conflict characteristics. With protectionist tendencies, big policy packages applied by the EU and the US are forcing different stakeholders to act in a unified direction, securing future supply chains and opportunities that green commitments bring in the medium and long term by making sure that there are short-term compensations for the necessary changes.

In an increasingly competitive scenario, the heavy level of subsidies implemented in those policies undermines developing countries’ natural advantages in the global race for a decarbonized economy. Here arises the question: how can Latin American countries use the window of opportunities and vast interest in its natural resources to leverage their socioeconomic and geopolitical status, instead of falling, once again, into the pitfall of commodities exportation we know so well? While there is no simple answer. what this article suggests is that Latin America’s unique environmental and political position can be best leveraged for development by the creation of a unified policy which produces direct incentives for climate mitigation comparable to the IRA and EU Green Deal. But, unlike them, this policy should not undermine the International Liberal Order (that promotes free trade and international cooperation), allowing for the introduction of international subsidies and existing improved capacities to accelerate the process, also fostering South-South cooperation.

Can we prevent history from repeating itself?

While commerce progressed throughout history, we had the materials the world needed. Our abundant natural conditions allowed us to provide it all: from gold and silver, to sugar, tobacco, coffee, soybeans, and oil, among many other resources. Even though throughout the “5 centuries of pillage”, as Galeano puts it, countries were able to reduce dependency by developing technology, sovereignty, and creating comparative advantages, several extractive institutions persisted. Latin American countries are still heavily reliant on the exportation of commodities with low aggregated value and thus face undesirable side effects on their economies and currencies from this natural resource curse, like the permanent crowding out of manufacturing.

Again, in a transition point to the world economy, we have the critical resources. For example, the green transition has led to an exponential increase in demand for lithium and copper: lithium-ion (li-ion) batteries are demanded mostly due to the rise of electric vehicles (EVs), and copper, on the other hand, is a key material in different core technologies of the energy transition–solar panels, wind turbines, power cables, and energy storage systems. S&P Global Market Intelligence projects its demand could outpace supply by around 50 million tonnes (Mt) per year by 2035.

Interestingly, South America holds more than half of global lithium reserves, mainly located in Argentina (21%) and Chile (11%). Bolivia also holds huge untapped lithium resources, although the lack of infrastructure hampers its economic viability. Copper is also abundant. Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, accounts for more than a quarter (27%) of global supply, while Peru accounts for 11%. Across the continent, close to half of the world’s copper is mined in Chile, Peru, Brazil, Panama and Mexico.

For Latin American lithium and copper, however, there is a blatant difference between reserves and refinery capacity. The value is mostly still aggregated internationally. China hosts 60% of the world’s lithium refining capacity for batteries, while Australia (producing 52% of the world’s lithium) has already put hundreds of millions of dollars toward supporting the lithium refining industry, aiming to reach 20 percent of global lithium refining by 2027. Further, the US also invests heavily seeking to diversify supply chains and reduce refinery dependency.

Currently, the Lithium Triangle countries appear to be at a crucial moment in their history, potentially “shifting away from resource-extraction-driven economic models” towards industrialisation that adds value to raw materials before exporting them. Though, there are still many additional challenges faced by Latin America when balancing the tensions this resource exploration will create. For example, there will likely be significant social and environmental challenges associated with large-scale mining, such as the displacement of local communities, water, air, and soil pollution, as well as the hazard of repeating previous catastrophes. Here, green finance executes a key role. ESG standards try to ensure mining operations are sustainable and generate tangible benefits for local communities. However, ESG alone might not be sufficient

A further challenge comes from the fragmented way in which Latin American countries are reacting to international interest and competition. With United States, European, and Chinese companies all interested in Latin America, the momentum is great. Bolivia and Chile believe that a push towards nationalization of those industries might be the best way to leverage the opportunity; though, Milei’s Argentina will set a market-oriented approach. The divergent responses, and most importantly, the very heterogeneous regulations, induce Latin American countries to compete with each other and lose bargaining power in the international landscape.

More than a Lithium cartel (similar to OPEC) that aims to protect Latin American producers from foreign powers, governments should think more broadly about how to create benefits. One way this can be achieved is by agreeing on supranational common policies which surpass the use of its critical minerals to push for a coordinated Green Agenda that advances diverse guidelines. Therefore, to make the most of this critical moment, Latin America will need to navigate distinct influences and ensure combining practices while addressing market uncertainties.

In the song “Latinoamérica”, Calle13 asserts Latin America’s resilience over time: “No se puede comprar al Viento. No se puede comprar el Sol” (You can’t buy the wind. You can’t buy the sun). Sadly, the competitive nature of climate action could be changing this. To sidestep the historical pitfall, Latin American leaders need to be aware of the rapid changes in the global geopolitical scene and take bold actions to guarantee its internal development as the world advances into a turning point.

Protectionist Measures and the End of a Global Hegemony

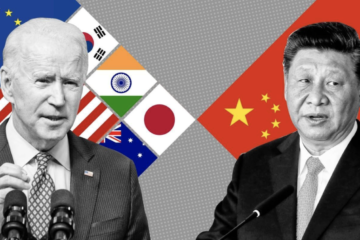

As the world shifts away from a single hegemony to a multipolar order, climate change actions that reflect the ability to make long-term decisions among fast-paced changes will be one of the defining factors of nations’ sovereignty in the near future. On an International lens, Latin America holds a critical geopolitical position in the contest of economic superpowers to control new markets and build global influence.

Foreseeing Latin America’s essential role in the energy transition, China is the leading influence in the region, and is in an advanced step of building a ‘grand coalition of the global periphery’. By enhancing relations with Latin America and the Caribbean, described in 2016’s white paper as “A Land Full of Vitality and Hope”, China sees its intention as one of ‘inclusive globalization’. Chinese leadership intends to build a co-prosperity sphere with economic growth and self-determination of development paths for all inside the “community of common-destiny”. In a more practical understanding, this means gaining access to Latin America’s growing markets and abundant resources to sustain economic growth. In addition to the economic ties built, China seeks to build a coalition in international politics that is both pro-China and at least implicitly anti-American.

Chinese economic statecraft and soft power in Latin America not only challenged US hegemony and amplified great power competition in the region, but more importantly for the scope of this article, it enabled the country to secure critical minerals and thus establish absolute leadership in sectors like EV batteries and solar panels.

To reduce dependency on Chinese factories, the United States enacted the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022. Much more than largely tax incentives meant to shape economic development in accordance with net-zero commitments, the IRA is one of the largest subsidy packages for clean energy in the history of the world. While presented as a climate-focused initiative, the IRA’s extensive subsidies distort global markets and mark a significant departure from the free market order. This protectionist approach has been firmly criticized by the EU, citing potential violations of WTO rules.

However, it seems contradictory to see the EU (and especially France) criticizing protectionism when they often face similar accusations of obstructing international competition. This can be seen when they declined the EU-Mercosur agreement under slogans of “concerns about the environment”, where in reality, pressure from domestic agriculture interest groups could have been the strongest factor in decision-making.

In fact, the EU is not really concerned with global competition in any way more than it is concerned with its own agenda of leading the energy transition. Through their own large policy programs under the Commission’s Green Deal Industrial Plan, boosted by the largest budget distribution ever implemented by the bloc (due to the NGEU-Next Generation EU), they prioritize and incentivize transformation. The IRA could create a subsidy war inside the continent, and is another influencing point to the potential creation of a Common Fiscal Policy in the Eurozone in the future.

The growing competitiveness of climate change policies between those aforementioned actors (but also worldwide) could have distinct implications. On the positive side, growing competition could ensure climate goals are achieved more quickly. They would only be catalyzed, however, in a fluid economic environment without trade tensions, which is unfortunately in the opposite direction to where we are heading.

As countries like the United States seek to reduce dependency on single actors, like China, they argue that cheap is not always the best: it can lead to economic security problems, exemplified by Europe’s struggle to replace its dependency on Russian gas. This explanation is rational, but at the same time, it discreetly shifts the focus of climate change policies from quick mitigation and collaboration to a zero-sum realism contest. As the IRA and the EU Green Deal unravel, their level of global cooperation and protectionism will tell us if they really prioritize the cutting of emissions – and whether they do this quickly (which means more supply from China) – or if the real target is not climate change abatement, but instead reindustrialisation.

Regardless of the true reasons for those policies, the increasingly competitive scenario of climate change could undermine Latin American countries’ natural advantage, if we let the difference in capacity for refineries and technology production consolidate our colonial-like position as purely raw commodity exporters.

Not only will subsidies lead relevant actors to reduce dependency on Latin America’s natural resources, but they are also vital to pay for the short-term costs of climate change policies – an aspect that will be significantly harder for individual Latin American countries to afford at the same level. According to Bechtel and Scheve (2013), public support for climate agreements is more sensitively correlated to the costs and distributed costs of the agreements. Not being able to compensate for those costs at the same scale will make it complicated for Latin America to coordinate opposing interest groups and approve climate change legislation or even elect politicians in favour of it.

Challenges and opportunities: coordinated action

Taking cognizance of the characteristics of an economic environment where China, the EU, and the United States are driving the global carbon cycle and energy transition – and the latter two show protectionist behaviour, to avoid falling behind in the Climate Change race, Latin America could benefit from enhanced cooperation on climate commitments and leveraging strategic resource advantages to tackle shared challenges.

Despite numerous institutional barriers, there are relevant and inspiring developments, including the increasing prominence of the Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC), with the potential to bridge the North-South divide given its focus on trying to enhance consensus and ambition.

Moreover, the Escazú agreement could be a solid stepstone to a larger common Green Policy, and help transform the fact that Latin America is the deadliest place in the world for environmental activists. For that to change, however, it is essential that more countries ratify the agreement, especially Peru and Brazil.

It is true that Latin America is historically overexploited, and that the region will indeed need financial support from other countries to act on climate change. However, as a civic duty, we cannot allow this to be consigned to the hollows of populist speech, deflecting responsibility from the actions Latin American governments should be taking. We need to reclaim our sovereignty by considering the best policies that could be executed now, and pressure governments to take bold actions for a better future.

Diego Rodrigues is from Minas Gerais, Brazil. He is an Economics student with a Global Development concentration at Grinnell College, currently studying International Relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science.