As we move away from Great Power politics, multipolarity begins to take centre-stage with various regional interests converging and clashing. States have begun to form their own paths away from the camps of the ‘West and the Rest’ that once defined geopolitics. But how do former superpowers like the U.S reconcile promoting an international order in diplomacy with states of great utility that dare to deny the principles of this order?

In June 2023, Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India went on a state visit to the United States of America. This official state visit presented a diplomatic honour to India, being the third country under the Biden administration to receive this public display of partnership after France and South Korea. This state visit included various elements, but most importantly the rare opportunity for Modi to address Congress as a foreign leader. Upon arrival at the White House, PM Modi was greeted by 7,000 cheering Indian Americans and went on to release a joint statement with President Biden on their increasing cooperation and collaboration in a wide array of fields.

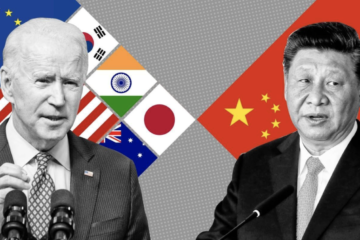

At the same time, uncertainty in the Indo-Pacific has led experts to contextualise this close relationship with the threat of China in the region. India’s border dispute with China in 2020 has been an important factor on their agenda in collaborating with the U.S. After this dispute, the Indian government banned 59 Chinese applications while also obstructing Chinese construction firms and rejecting Huawei as India’s 5G provider. Similarly, it seems to be clear that the U.S is increasingly concerned with the position of China in the region and the threats it poses to the security of the Indo-Pacific. In his campaign, Biden explicitly mentioned working closely with India to promote ‘peace and stability’ without the threat of neighbours such as China. His administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy has clearly signalled out the PRC as a challenge to the rules-based international order with their ‘coercion and aggression’, citing a partnership with India to promote stability in the region. Furthermore, the Vice Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee pointed out the overlap of economic and security issues between India and the U.S due to ‘the growing hostility of the Chinese Communist Party’.

When Biden described the India-U.S relationship as the most consequential in the world, it is evident that China was in the backdrop of that statement as Tamanna Salikuddinn from the US Institute of Peace analyses. This is not to deny India’s rising global significance, overtaking the U.K last year to become the fifth largest economy in the world. There are other pertinent factors fuelling these bilateral ties such as the 4 million people of Indian origin in the U.S and the fact that U.S is India’s largest trading partner. However, India’s usefulness to the U.S only grows as geopolitical anxieties develop further about China, with a senior administration official telling media sources that China is an ‘undeniable factor’ in this bilateral relationship. Indeed, Tourangbam from the Indian Foreign Affairs Journal points out how despite changes in administration in these two states, the bilateral relationship has persevered because of the ‘seesaw of Asian geopolitics’ that binds them closely together.

Thus, Modi’s recent visit saw an affirmation of the interconnectedness of the two states, extending it further on a grand scale. Their joint statement developed collaboration in areas such as technology, climate action, educational institutions, and earmarked increased investment. Interestingly, they strengthened their defence partnership with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding for the manufacturing of jet engines in India with transferred U.S jet engine technology and also confirmed India as a ‘hub’ for U.S Navy ships maintenance and repair. Their defence partnership also included a ‘Defence Acceleration Ecosystem’ that will build on their technology sharing and defence industrial cooperation through innovative research. This extensive strengthening of defence and military focus suggests that India’s importance to the U.S is related to its role in being a counterweight to China. Even non-defense points of collaboration decided on this state visit such as quantum computing, A.I and 5G wireless networks are all fields that China leads in, displaying once again how China remains a key priority in these bilateral ties.

The principles of realpolitik seem to be a commanding force in dictating the U.S approach to the Indo-Pacific, highlighting their priorities in strategic interest and a favourable balance of power. Yet, the bilateral ties between the U.S and India have an ideological element that presents Biden with the dilemma mentioned in this article’s introduction. On the one hand, the U.S India partnership has been lorded as one between democracies that enshrine human rights, democratic institutions and international law. Simultaneously, India has been ideologically opposed to the U.S on key issues that contradict this. India has refused to condemn Russia’s war in Ukraine, continuing to be an importer of Russian oil and weaponry. The U.S. State Department has also condemned India’s decline in freedom of expression and violence against minorities, while New Delhi dismissed this report as partial. Modi’s state visit was not only protested, but his address to Congress boycotted as 70 representatives from Congress wrote a letter to Biden on India’s democratic backsliding.

Yet when questioned during their recent visit, both Modi and Biden dodged the questions and feigned ignorance. Biden simply mentioned that both leaders had spoken about democratic values in a ‘straightforward’ manner, while Modi said he was ’surprised’ with the critique that minorities are discriminated against in India. Alongside this, both states affirmed their belief in the principles of ‘democracy, freedom, and the rule of law’ and a rules-based international order despite India’s human rights violations and relations with Russia contradicting this. Consequently, India has strengthened its historical position of independence, as its government maintains its foreign policy of nonalignment and increasingly antidemocratic domestic policies.

India is the world’s largest democracy, and holds elections regularly. Its current government is not in power undemocratically, but its actions are in obvious contradiction with the ideals that the U.S is attempting to promote through this partnership. However, this rhetoric of democratic collaboration is instrumental, especially when positioning the India-U.S relationship in opposition to China. By rationalising the US/ India partnership under ideological similarities, the US may be establishing a moral barricade of democratic principles and a rules-based order in forceful opposition to China.

Hence, the US provides an alternative to China’s power in the Indo-Pacific and simultaneously attempts to veil its strategic interests as secondary to ideology in its partnership with India. In Tourangbam’s words, their ideological similarities are only ‘propagated as the glue that binds the two countries’ when it is instead the Indo-Pacific balance of power that drives this convergence. The American courtship of India stomachs the ideological contradictions it may have with India in place of the immense usefulness of a strategic partnership because of the region’s geopolitics. Ultimately, it is that which seems to have solidified bilateral ties between India and the US, rather than ‘the romance of shared values’ as Barkha Dutt from the Washington Post writes.

While seemingly localised to the Indo-Pacific region, the bilateral relationship between India and the U.S can represent a shift in international affairs. As the U.S begins to overlook significant ideological disagreements with partners to prioritise strategic interest, it helps usher in a new era. This international order has begun to allow for independence, flexibility and multipolarity in geopolitics, escorting out the etiquette of ideology that dictated public diplomacy in the Western-based international order.